Here is an article about the Nyumbani Village in Kitui.

Here is an article about the Nyumbani Village in Kitui.Open Access Article Originally Published: September 29, 2006 - Fr. D'Agostino died in November 2006

Despite enormous natural wealth both human and material, the continent, which straddles the Equator from Casablanca to Capetown, has a long history of oppression, from tribal conflicts to the slave trade to colonialism to seemingly countless despotic governments through the latter half of the 20th century.

And now the most ruthless and cruel oppressor of all is laying waste to a generation of people by the millions; and in its wake, it is leaving behind anywhere from 12-to-25 million orphans, a number soon to grow to 18 or 40 million, depending on whose numbers you choose to believe.

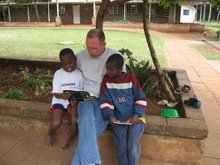

A village is being built by Father Angelo D'Agostino, a medical doctor, psychiatrist and Jesuit priest.

Father Angelo was in Washington, D.C. last week to be honored for his work in trying to improve the lot of the AIDS orphans of Africa by developing the concept behind and funding for Nyumbani (pronounced 'knee-um-bahn-ee' and meaning 'home' in Swahili) village in Kenya. Inspired by the Gaviotas experiment in Columbia, he set out to create a model eco-village that will house 1000 orphans and 250 elders (grandmothers, usually) who will care for and mentor the children.

The goal is a sustaining community in terms of both food production, energy and use of local resources. Many of the 100 rammed earth-block homes will be powered by photovoltaic panels. The village has used an ancient technique to assure a supply of clean water. It has planted some 400 acres of Jatropha Curcas trees and is in negotiations with the Kenyan government for more. Even the human waste -- both liquid and fecal -- are collected and eventually turned into fertilizer and safe, composted humus.

Father Angelo's efforts to address the human toll of the AIDS pandemic in Africa began 14 years ago in the slums of Nairobi, setting up a orphanage to take in and care for parent-less children. Then two years ago, he conceived of the idea of a model village in which children could grow and some semblance of the family unit could be preserved.

The government of Kenya donated 1000 acres of arid scrub land an hour's drive east of the capitol on land inhabited by the Kamba tribe. Between a half million Euro donation from the Vatican -- which he refers to as a "miracle" -- and another half million Euros from another governmental body in Italy, D'Agostino and his aid organization were able to break ground on Nyumbani village.

His vision involved satisfying three major objectives: reduce poverty in the community, be ecologically friendly so that not only did it not degrade the environment, but would enhance it. Lastly, it had to be "self-sustaining".

He explained that he learned from his organization's work in the slums of Nairobi that surviving grandparents of AIDS orphans often were attempting to care for 10-15 children in a land where Social Security isn't available. The effect is devastating poverty for everyone.

As a result, Nyumbani village includes a carpentry shop where children are taught wood working skills. There is also an agri-forestry program that includes the planting and cultivation of both jatropha and vegetable crops. The Father noted that the government of Kenya has already agreed to buy any excess jatropha oil, which can be used as a biodiesel fuel, from the village to use in electric power generators in the energy-starved northern part of the country.

Because the land on which the village is located is semi-arid, the first prerequisite was to find water and here Father Angelo takes great pride in explaining how they solved the problem in a place that has been in a drought the last ten years, and received virtually no rain the last three.

He carefully explained how his people used an ancient technology called 'sand dams' to capture and replenish their local wells. Digging series of seven deep trenches across dry stream beds, they built submerged stone dams, the tops of which are no more than a foot above the surface of the river bed. The dams work by slowing the flow of the water, allowing it to be absorbed by the sand and then be directed by the underground stone dams toward the sub soils along the stream banks where wells had been dug.

With the sand dams in place and the shallow wells dug -- they had to dig down thirty feet to reach water -- the village next needed the rains to come. They did, miraculously, on Palm Sunday this year after an absence of three years. And the dams worked. The wells along the banks were recharged and water rose in them to just five feet below the surface.

Using drip irrigation, the village was able to grow and sell 16 varieties of fruits and vegetables in the local market. They also made available small, one meter by one meter plots of ground to local villagers so they could grow vegetable as well. Nyumbani supplied the ground, the water and in some cases the tomato seedlings for free. The only stipulation is that in the middle of each plot the farmer had to plant a tree as part of the villages reforestation program.

"When they water their tomato plant, they water the tree as well," he said.

Fifty-five of the eventual 100 homes have already been completed, as has the five building school complex. There is also a clinic and a three-cell police station, an eight-room guest house, an environmental center and a three-building vocational training center.

Father Angelo told EV World that while the Kenyan government is very supportive and excited about the possibilities demonstrated by Nyumbani village, he also acknowledged that the large, mainstream aid agencies "just can't think outside the box" when it comes to a project like this.

"Hopefully, they'll wake up someday," he said.

The same might be said of the rest of us. Nyumbani clearly suggests that there are affordable, humane ways to tackle the problems created by the AIDS pandemic in Africa, especially that of the survivors, the young and the old. Here is a program that I think both conservatives and liberals can love. It encourages local and individual self-reliance in a nurturing, family-oriented environment.

There is much more to my interview with Father D'Agostino and I encourage you to listen to the entire 30-minute program, as well as to visit the Nyumbani Village web site. There are supporting chapters of Nyumbani in the U.S., UK, Italy and Kenya if you wish to get involved in this worthwhile effort.

Finally, if you really want to get your hand dirty, Father Angelo is also looking for volunteers with certain skills who are willing to spend at least 3 months at the village working with the families there.