Well I was expecting a long journey to the land of the Turkana. It was. Benson Lotiang’a is a friend I met in the kitui village a year or so ago and we had always planned to head to his homeland in the north at some point. His mother has been sick from a number of ailments, the major one, epilepsy. It is difficult to get medications and control the problem here in Kenya. Of course, as you might expect, the tribe often thought of her as possessed or carrying a demon because of the condition and her convulsions, etc. And so Ben and I decided on some dates and mode of transportation. To fly would cost the two of us about $750 total. And so we opted for the long bus ride from Nairobi to Kakoma at a cost of about $100 total. The bus was scheduled to leave at 7 am on Thursday morning (we know that actually means 9am) and so we decided to stay the night near the bus “station” in Eastleigh. We stayed in the Somali section of town in a Somali Guest House. It reminded me of movies I’d seen of Istanbul. Long cement hallways, dark figures passing silently, and the room was simple but with a toilet and hole in the floor for a shower. There was an electric heater attached to the showerhead but it sparked when Benson turned it on. We took cold showers, not wanting to be electrocuted. We boarded the bus in the morning and departed at about 9:00 a.m. It was a long journey over good roads until Eldorett. We passed IDP camps of people who were burned out of their homes during the post-election violence and were still stranded in white tents off the main roads. We made periodic stops through the night and bought cookies and soda etc. I was afraid to eat most foods although I took a mandazi and some tea at some places.

We finally reached Lodwar, in the north of Kenya, a large town in comparison. We were to head to Kakoma from there but word was out there had been violence there overnight and we should not travel at night. We stayed on the bus in Lodwar until daybreak and at about 8:30am, we headed to Kakoma. We had been traveling in a convoy of three buses for safety. There were marauders and thieves along the way. We were not too far from the borders of Ethiopia, Uganda and Sudan. Gunrunners and bandits often stopped buses and travelers at night in the lonely hills and mountainous areas. And so we left at daylight. We were told that the soldiers in Kakoma had shot and killed two protesters the night before and people were angry in the streets. The people were protesting jobs given out to outsiders from Nairobi etc instead of to locals. The demonstration had gotten violent and shots were fired. There are no warning shots; the soldiers aim to kill. And so they did. When our bus arrived, we were greeted by large crowds pounding on the side of our bus and yelling at us. I hid my white face. The UN people and those NGOs who hired out of towners were white and I didn’t want to be mistaken for a UN manager. The bus picked up pace and headed to the police station where we were taken off the bus. We got a bicycle ride to a guesthouse on the other side of town and tried to get the full story of the security in the area. Eventually we heard that things calmed, protest activities delayed until an MP came to speak to the crowds and until the funerals amped up the crowd again. We would be gone by then, thankfully. Still, I was warned to do any business in town quickly and get back to the lodge so as not to be mistaken for UN. I had people approach me in the streets to argue about hiring issues. I realized they thought I was from an NGO or the UN.

The next morning we began our walk to the Turkana village of Ben’s mom, brother and sister. Already the heat was oppressive. Along the way Ben was greeted by old friends. We passed bare-chested women carrying branches or water jugs on their heads. We passed Turkana warriors wearing only a blanket around their shoulders and carrying a carved walking stick and small stool to sit on. All were friendly enough and nodded or spoke a Turkana greeting “Ajuka”. Clothes are optional in the village. Traditionally the women and the men were uncovered and the tradition continued. One becomes used to it. When we arrived at the small plot where Ben’s mom lived, there were no adults around. We stuck our heads in the four small huts in the area. Ben’s sister appeared and finally his mother. We greeted her quickly and then went to be seated in one of the other huts to be welcomed by her. There was no affection or emotion shown. It was like we were salesmen coming to present our products. Ben’s mom was sick. She has been sick for most of Ben’s life and she was bitter and wanted to die. “Why should I live this way?” Her face was badly burned from falling into the fire during an epileptic fit. She was unaware that her face was being burned as well as her hands and legs. She suffered too from malaria and some other diseases. She was thin and week and looked to be close to death in both appearance and emotions. As Ben talked to her about her health etc. we heard wailing and screaming in the hut next to Ben’s moms. The neighbor woman’s child had just died and the woman was hysterical at the death. It was not uncommon. People die in this area from diseases and from starvation. Ben had watched his grandmother starve to death. He also, as a child himself, found a boy by the river who had died of starvation. He told me stories of people eating grass like cattle and boiling water to have something in their stomachs. There are no latrines and human feces can be seen and smelled everywhere. The drought had taken its toll on both humans and animals.

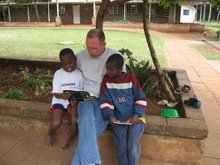

Back to our visit. I was greeted by Ben’s mom but I knew she was unhappy. Eventually Ben translated that his mom was upset. The tradition of the Turkana is such that when a special guest comes, like a white man, it is a blessing. In good days they would have slaughtered a goat or given me a goat, something to show that I was welcomed. But they had nothing to give me, nothing to share. I tried to make Ben see and translate that this experience, their welcoming me into their house was the gift and that in America, it was the visitor that brought a housewarming gift. I had brought nothing. Eventually she asked if I could take tea. Ben had told her I could take anything like water or rice for fear of typhoid or other diseases. I had brought a bottle of water. I told her I would be grateful for tea so it was made with powdered milk they found. The visit continued and I took some photos and we left to walk to the refugee camps along the river. We promised to return the next morning, hoping to see Ben’s brother.

Some background – Ben’s father died when Ben was young. His mom could do little to care for him because of her illness. The uncle and other relatives were abusive and Ben left for the streets at an early age. He was convinced that he could do better on his own, even running guns or selling drugs. Thankfully he was taken into an orphanage by some Irish sisters and lived there, begging for food and school fees. He also lived in a home for street boys as he got older and it was there that his academic education began. His mom never knew that he went to school. She never bought him anything like a pencil or trousers. She could not care for him and he remembers that fact. So he sits, sad at her lack of mothering. She sits, sad at the departure of a son that should be caring for a dying mother. They are both caught, both correct. We left for the refugee camps, talking to his sister on how we could help out both his sister and his dying mother. (More to come but here is some history, etc.)

We finally reached Lodwar, in the north of Kenya, a large town in comparison. We were to head to Kakoma from there but word was out there had been violence there overnight and we should not travel at night. We stayed on the bus in Lodwar until daybreak and at about 8:30am, we headed to Kakoma. We had been traveling in a convoy of three buses for safety. There were marauders and thieves along the way. We were not too far from the borders of Ethiopia, Uganda and Sudan. Gunrunners and bandits often stopped buses and travelers at night in the lonely hills and mountainous areas. And so we left at daylight. We were told that the soldiers in Kakoma had shot and killed two protesters the night before and people were angry in the streets. The people were protesting jobs given out to outsiders from Nairobi etc instead of to locals. The demonstration had gotten violent and shots were fired. There are no warning shots; the soldiers aim to kill. And so they did. When our bus arrived, we were greeted by large crowds pounding on the side of our bus and yelling at us. I hid my white face. The UN people and those NGOs who hired out of towners were white and I didn’t want to be mistaken for a UN manager. The bus picked up pace and headed to the police station where we were taken off the bus. We got a bicycle ride to a guesthouse on the other side of town and tried to get the full story of the security in the area. Eventually we heard that things calmed, protest activities delayed until an MP came to speak to the crowds and until the funerals amped up the crowd again. We would be gone by then, thankfully. Still, I was warned to do any business in town quickly and get back to the lodge so as not to be mistaken for UN. I had people approach me in the streets to argue about hiring issues. I realized they thought I was from an NGO or the UN.

The next morning we began our walk to the Turkana village of Ben’s mom, brother and sister. Already the heat was oppressive. Along the way Ben was greeted by old friends. We passed bare-chested women carrying branches or water jugs on their heads. We passed Turkana warriors wearing only a blanket around their shoulders and carrying a carved walking stick and small stool to sit on. All were friendly enough and nodded or spoke a Turkana greeting “Ajuka”. Clothes are optional in the village. Traditionally the women and the men were uncovered and the tradition continued. One becomes used to it. When we arrived at the small plot where Ben’s mom lived, there were no adults around. We stuck our heads in the four small huts in the area. Ben’s sister appeared and finally his mother. We greeted her quickly and then went to be seated in one of the other huts to be welcomed by her. There was no affection or emotion shown. It was like we were salesmen coming to present our products. Ben’s mom was sick. She has been sick for most of Ben’s life and she was bitter and wanted to die. “Why should I live this way?” Her face was badly burned from falling into the fire during an epileptic fit. She was unaware that her face was being burned as well as her hands and legs. She suffered too from malaria and some other diseases. She was thin and week and looked to be close to death in both appearance and emotions. As Ben talked to her about her health etc. we heard wailing and screaming in the hut next to Ben’s moms. The neighbor woman’s child had just died and the woman was hysterical at the death. It was not uncommon. People die in this area from diseases and from starvation. Ben had watched his grandmother starve to death. He also, as a child himself, found a boy by the river who had died of starvation. He told me stories of people eating grass like cattle and boiling water to have something in their stomachs. There are no latrines and human feces can be seen and smelled everywhere. The drought had taken its toll on both humans and animals.

Back to our visit. I was greeted by Ben’s mom but I knew she was unhappy. Eventually Ben translated that his mom was upset. The tradition of the Turkana is such that when a special guest comes, like a white man, it is a blessing. In good days they would have slaughtered a goat or given me a goat, something to show that I was welcomed. But they had nothing to give me, nothing to share. I tried to make Ben see and translate that this experience, their welcoming me into their house was the gift and that in America, it was the visitor that brought a housewarming gift. I had brought nothing. Eventually she asked if I could take tea. Ben had told her I could take anything like water or rice for fear of typhoid or other diseases. I had brought a bottle of water. I told her I would be grateful for tea so it was made with powdered milk they found. The visit continued and I took some photos and we left to walk to the refugee camps along the river. We promised to return the next morning, hoping to see Ben’s brother.

Some background – Ben’s father died when Ben was young. His mom could do little to care for him because of her illness. The uncle and other relatives were abusive and Ben left for the streets at an early age. He was convinced that he could do better on his own, even running guns or selling drugs. Thankfully he was taken into an orphanage by some Irish sisters and lived there, begging for food and school fees. He also lived in a home for street boys as he got older and it was there that his academic education began. His mom never knew that he went to school. She never bought him anything like a pencil or trousers. She could not care for him and he remembers that fact. So he sits, sad at her lack of mothering. She sits, sad at the departure of a son that should be caring for a dying mother. They are both caught, both correct. We left for the refugee camps, talking to his sister on how we could help out both his sister and his dying mother. (More to come but here is some history, etc.)

Some Turkana History

So recapping, a 26 hour trek to the land of the Turkana in northern Kenya. Here is a some background on the history of the area and the tribe. Around 2 million–3 million years ago, the lake was larger and the area more fertile, making it a centre for early hominins. Richard Leakey has led numerous anthropological digs in the area which have led to many important discoveries of hominin remains. The two-million-year-old Skull 1470 was found in 1972. It was originally thought to be Homo habilis, but the scientific name Homo rudolfensis derived from the old name of the Lake Rudolf, was proposed in 1986 by V. P. Alexeev. In 1984, the Turkana Boy, a nearly complete skeleton of a Homo erectus boy was discovered by Kamoya Kimeu. More recently, Meave Leakey discovered a 3,500,000-year-old skull there, named Kenyanthropus platyops, which means "The Flat-Faced Man of Kenya".

The population of the Turkana tribe ranges around 350,000, and they are a part of the larger Nilotic group of tribes (along with the Samburu and the Masai). They are a very traditional tribe; with most of their people still living rural lives as they have for generations. You can find the Turkana territory near the shores of Lake Turkana in the very dry regions of northwest Kenya. They rely heavily on the rainy seasons and the 2 rivers that run through their land for water. Water can be very scarce. The harsh environment creates a great deal of tension between tribes, making the Turkana tribe a very fierce and aggressive people. Their language is called Turkana, and has a separate dialect for the northern and southern regions of their territory.

Turkana History.

Around 400 years ago, the Turkana tribes migrated into Kenya from north-eastern Uganda. During the colonial period and even after Kenyan independence, the Turkana have mostly been left alone. They are largely untouched by the influence of missionaries or other aspects of western civilization. And so their history is not marked by many modern events, and they are still the same as they have always been.

Turkana Culture and Family

Livestock are the center of Turkana economics, representing both a food supply and wealth. Camels, cows and goats are the favored animals, along with some donkeys and sheep.

As a nomadic people, the social structure is very loose and flexible. This is necessary, given the constant movement of families as they search for better grazing land and water. Each family is a self-contained social unit, with 4 or 5 families sometimes grazing together. Families can get quite large as married sons (and their wives and children) will stay with their father's family. Initiation into adulthood is a somewhat subdued affair with minor rituals marking the event for boys every 4 years. Girls are considered adults once they are married. Unlike most other tribes, there is no circumcision among the Turkana. Age sets exist but are not particularly important.

Turkana men can take as many wives as they have cattle to buy them with. A woman can cost dozens of cows, goats, camels or sheep. Men without enough livestock sometimes resort to "stealing" a bride, though it’s mainly symbolic with both sides agreeing to the theft. A marriage is only considered to be finalized after the first child has begun to walk, usually around 3 years after the initial ceremony.

As a nomadic people, the social structure is very loose and flexible. This is necessary, given the constant movement of families as they search for better grazing land and water. Each family is a self-contained social unit, with 4 or 5 families sometimes grazing together. Families can get quite large as married sons (and their wives and children) will stay with their father's family. Initiation into adulthood is a somewhat subdued affair with minor rituals marking the event for boys every 4 years. Girls are considered adults once they are married. Unlike most other tribes, there is no circumcision among the Turkana. Age sets exist but are not particularly important.

Turkana men can take as many wives as they have cattle to buy them with. A woman can cost dozens of cows, goats, camels or sheep. Men without enough livestock sometimes resort to "stealing" a bride, though it’s mainly symbolic with both sides agreeing to the theft. A marriage is only considered to be finalized after the first child has begun to walk, usually around 3 years after the initial ceremony.

Turkana Religion

Most of Kenya's native people have had their religious ways pushed aside by Christianity. The Turkana tribe is an exception, with most people still keeping to their traditional beliefs. Their god is called Akuj, who is prayed to directly or through the spirits of ancestors. He is not part of everyday life for the Turkana and is usually only turned to when rain is needed. Animal sacrifices are common during drought periods, to please Akuj.

Turkana Tribe of Kenya

Turkana Tribe of Kenya

Turkana tribe is the second largest pastoral community in Kenya. This nomadic community moved to Kenya from Karamojong in eastern Uganda. The Turkana tribe occupies the semi Desert Turkana District in the Rift valley province of Kenya. Like the Maasai and tribes, Turkana people keeps herds of cattle, goats and Camel. Livestock is a very important part of the Turkana people. Their animals are the main source of income and food. However, recurring drought in Turkana district adversely affect the nomadic livelihood.

Like the Maasai and Samburu, the Turkana people are very colorful. Turkana people adorn themselves with colorful necklace and bracelets. Their decorations are made of red, yellow and brown colored beads. Cattle's rustling is common in Turkana district and round its border with Uganda, Sudan and Ethiopia. Tribes inhabiting this area are often involved in tribal fights for livestock and water. Cattle's rustling has been a common phenomenon for many decades and appears to be a sort of cultural game for the nomadic communities living in parts of the Rift valley and its surroundings. With the proliferation of small arms, cattle's rustling has become more dangerous and the Kenyan government has intervened in solving the problem.

More to come regarding Ed and Ben's adventure.